Before diving into this blog post, allow me to introduce myself. My name is Mebin Thattil. I'm a student at PES University, Bangalore, and I'm part of HSP, PIL, and ACM. Over the summer after my first year, I participated in the Google Summer of Code (GSoC) program. Before GSoC, I didn't have much experience with open source. Now, don't let the creation date of my GitHub account fool you. Even though I have had my account since 2018, I hadn't contributed to any major open source projects.

The reason I wanted to give this introduction is so that anyone reading this understands that if I can do it, so can you. Don't create an artificial barrier in your mind and shy away from GSoC or open source contributions thinking that you're not good enough. I personally had this notion and felt that I wasn't good enough to contribute to open source. I always thought GSoC was something I could try in my second year and that if I didn't get accepted, I'd try again the following year. But fortunately, my assumptions turned out to be wrong. It was my seniors who encouraged me to try GSoC and made me realize that I had nothing to lose by trying. So I decided to give it a shot - and I'm glad I did!

Open source is a pretty self-explanatory term. It's a way to share your work with the world and encourages others to build on it. Much of modern software would be impossible without open source, since many of the tools they use under the hood are open source; not using them would mean reinventing the wheel repeatedly, often poorly.

Let me explain the "shabby reinvention of the wheel" in a little more detail. Say you're working for a company that is going to make a video-editing application. Writing a lot of the under-the-hood tools for this, like video converters would be painful. And considering that your main goal is to get the video editor out soon, you can only allocate limited time to developing tools like converters, encoders, and decoders. So you'd naturally end up doing a poor job, missing edge cases, or skipping optimizations.

Here comes the true beauty of open source: you could use a project like FFmpeg and get much of the under-the-hood heavy lifting done. FFmpeg is developed separately and doesn't have the same hard deadlines you do for shipping your product. As a result, there's a good chance the code is well written - and the wider community acts as an extensive set of reviewers. This helps ensure code is high quality, efficient, and safe.

Lucky for you, open source exists - so you can use FFmpeg. But after using it, you might realize there are additional features you need. Open source gives you the freedom to build on top of tools like this and add the features you want.

Now that you're (hopefully) convinced that open source makes the world better, let me explain what GSoC is.

GSoC, or Google Summer of Code, is a program Google runs to get students involved in open source projects. It's a great opportunity to learn about open source and contribute to it. It's also a great way to get exposure to the open source community, meet like-minded people, and build a network.

All the work you do during GSoC is open source. Having worked as a GSoC contributor looks good on your resume - Google's name helps your application stand out. It's also a good signal to recruiters that you can work in a team, write production-quality code, and have real world experience.

GSoC also pays reasonably well: you could earn anywhere from $750 to $6,000. The stipend depends on the size of the project and the country you reside in during the program. Stipends are paid by Google, not by the organization. In a way, Google acts as a marketplace connecting organizations and students. Google pays stipends both to contributors and to the organizations they work with.

Working on a personal project is vastly different from how code is written in a company or team setting.

The first major challenge I faced was learning to read and make sense of large codebases. When you write code for a personal or college project, you usually start with a clean slate, so you write more than you read. That reverses when you work with an open source project or as part of an organization: you'll often need to build on a pre-existing product, and the ability to scan and understand large codebases becomes crucial.

Navigating those codebases was initially intimidating, but the more time I spent in the code, the easier it became. Soon I reached a point where I felt comfortable and could build new features on top of the existing code.

Another big change is that any additional code you write should be well-documented. Tomorrow, people will build on top of your work, so it's your responsibility to write code that's clear and easy to extend.

Working in an organization also forces you to think from the end-user's perspective and account for varied user needs. For example: I built a finance tracker last year that parses my bank statements and categorizes my finances. I wrote it to parse only SBI bank statements because that's where my account is, so I didn't worry about other banks. But if I'd built this as part of GSoC or for an organization, I'd need to support users from many banks. Also, my finance app is mostly CLI-based - fine for me, but intimidating for non-tech-savvy users. In a professional or open source setting, inclusivity becomes a priority.

Another big one is effective communication. As a global program, GSoC often involves mentors and contributors across different time zones. That limits opportunities for real-time conversations, so it's essential to communicate clearly and concisely. Without that clarity, miscommunication can cause delays and wasted effort. Unlike on-site internships, GSoC is remote and relies heavily on asynchronous channels like email, GitHub, and Matrix, so strong written communication skills are crucial.

Those were just some of my major learnings; there are many more I haven't covered here.

The organization I contributed to over the summer was SugarLabs. SugarLabs is a global non-profit with a mission close to my heart: improving accessible education for children globally through technology. SugarLabs is best known for its Sugar learning platform. Sugar powers the One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) laptops. Sugar is essentially a desktop environment that sits on top of Linux and provides a set of activities that can run within it.

This is what the OLPC laptops looks like:

The first time I heard about SugarLabs was while browsing the orgs page on GSoC xD. Prior to that, I had no idea SugarLabs existed.

One piece of advice I'd give to anyone applying for GSoC is to choose an organization whose work genuinely interests you or makes a meaningful impact. Passion and curiosity are your greatest strengths. Try to find a project you'd be excited to work on even if you weren't paid. This mindset can make a big difference.

I started looking into GSoC and organizations around the second week of February, a few weeks before orgs were officially announced. I spent several days setting up and tinkering with Sugar, trying different activities. That helped me understand what the product did well and what could be improved.

Now, let's talk contributions. When you're new to a codebase and community, it's easier to start by picking up issues tagged "good first issue." Another way to contribute is to make small quality-of-life improvements to the project - for example, adding keyboard shortcuts for frequently used actions (one of my pre-GSoC PRs was exactly that).

Once you're familiar with the community and codebase, check the organization's GSoC idea list (if they have one). That's a list of projects orgs propose for contributors to pick up over the summer. You can propose your own idea, but that's usually harder because you'll need to find and convince a mentor to support it.

Something that helped my application was having an almost-working demo of the project I wanted to work on. That gave both me and my mentors confidence that I could complete the project over the summer.

Before selections, I had opened about four PRs and worked on the demo (some demo work wasn't submitted as PRs).

My GSoC proposal was based on an idea from the organization's project list. The proposal was to modernize the Speak activity by swapping out the old robotic speech synthesis for a more natural-sounding TTS model, and to use a combination of a Small Language Model (SLM) running locally and a Large Language Model (LLM) hosted in the cloud to power chatbot mode.

Here are some of the challenging and interesting problems we needed to solve:

Before implementing the activity, the first few weeks were spent testing and benchmarking different models to see which worked best for our use case.

By far the trickiest one to benchmark was the SLM. For the SLM, it's ideal to start with a very small model and work up from there by fine-tuning, quantizing, and converting to formats like GGUF for performance gains. After some research I started with TinyLLaMA 1.1B. After fine-tuning, quantizing, and converting to GGUF, the model was still too big for our use case and did not perform well. I repeated this process on many other models and ended up creating a script to automate the pipeline.

The sizes of those models were still too large, so I realized there were two options: quantize more aggressively or pick a smaller model. I initially tried heavier quantization, but that degraded quality from bad to awful.

So I tried even smaller models. I experimented with LLaMA-135M. After fine-tuning, quantization, and converting to GGUF, the model was lightweight, but responses were still poor (though not awful). I tuned it further and ended up with multiple models to compare. You can find them on my Hugging Face page. To review and grade responses without asking mentors to run all 16 models locally, I created an SLM benchmark Streamlit app to compare outputs.

TTS was easier to benchmark. After testing a few models we settled on Kokoro. Kokoro was lightweight, open source, supported multiple languages, and could mix multiple stock voices to create new ones - effectively enabling many voice options.

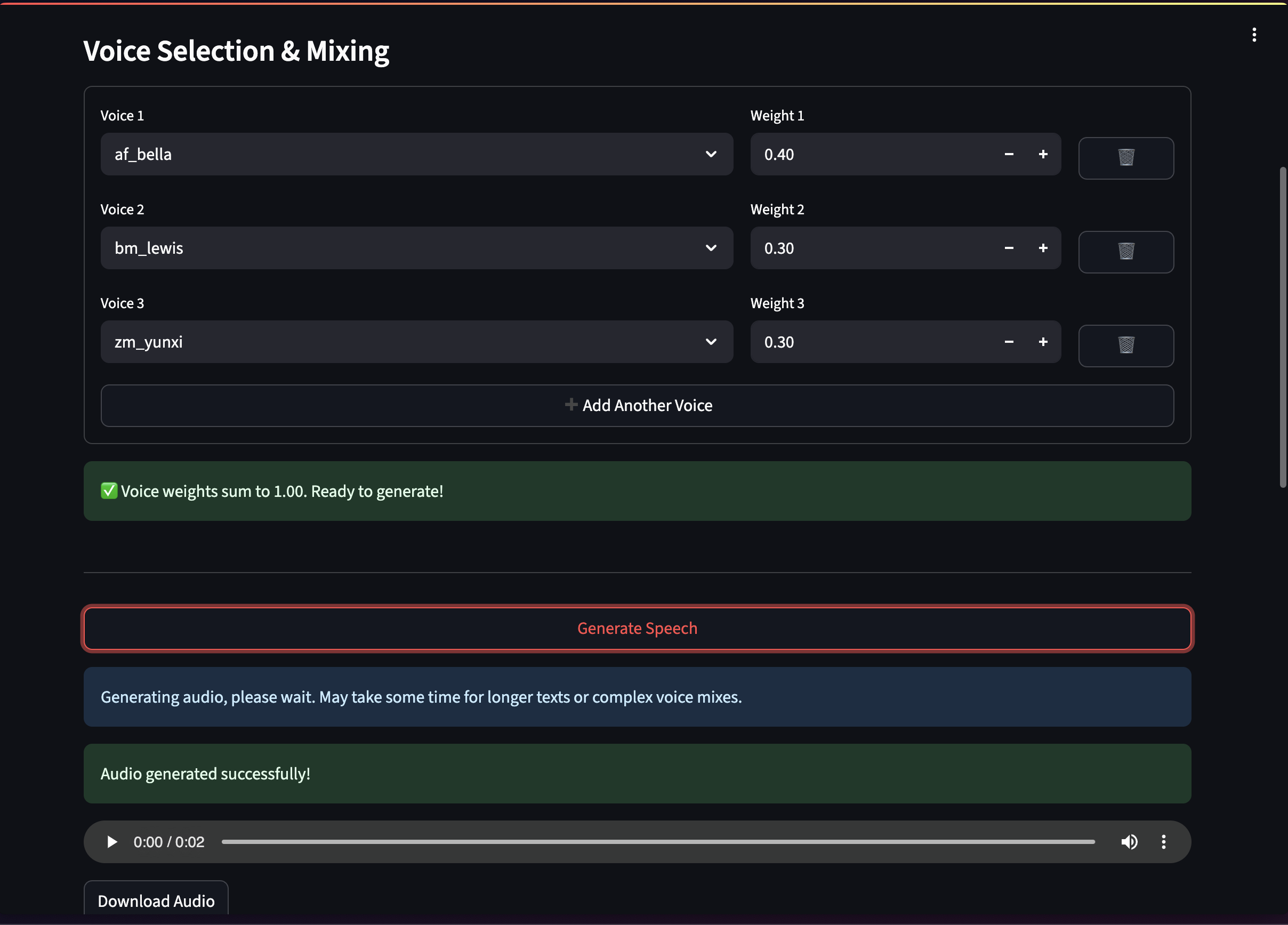

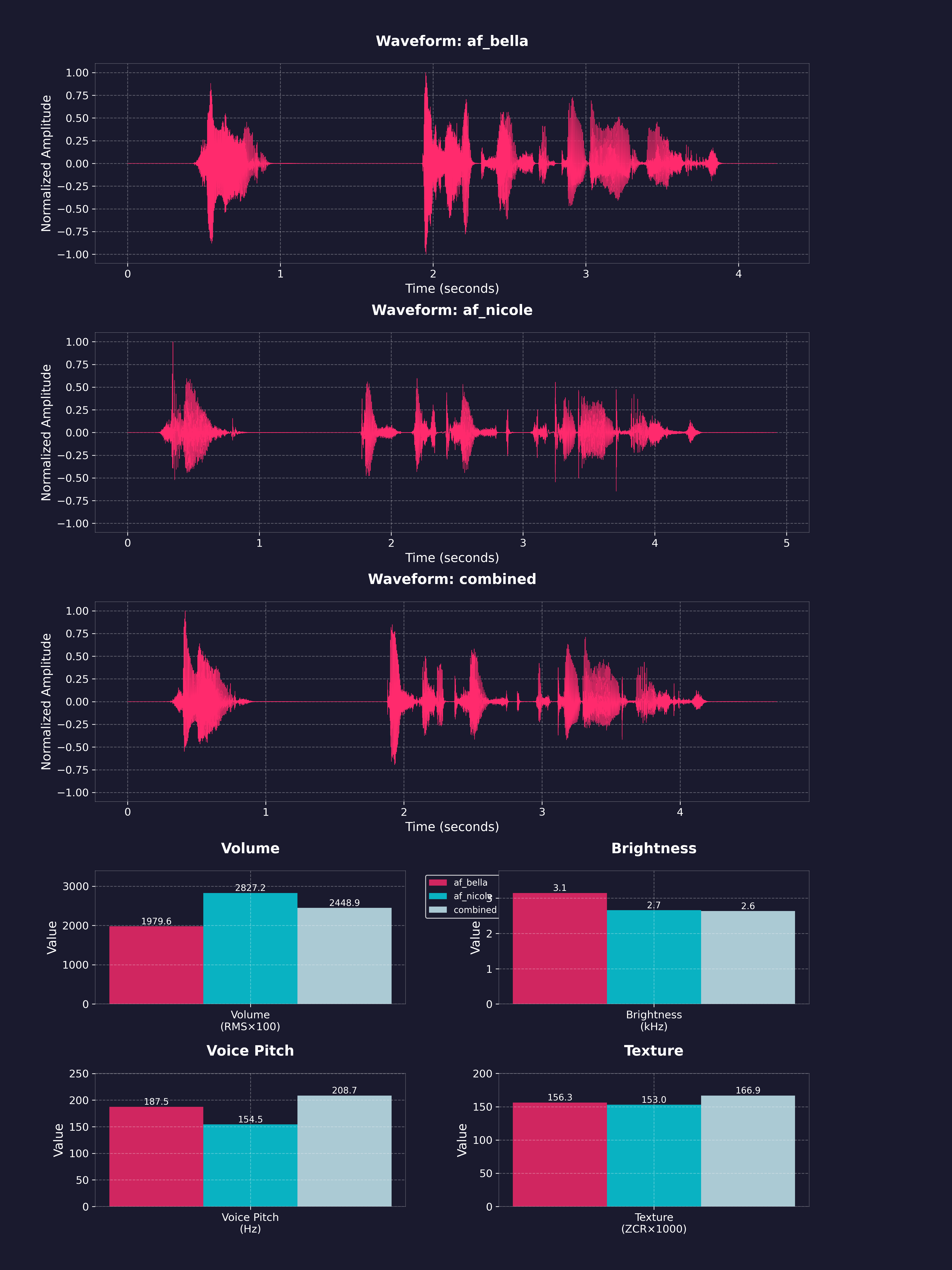

To test these voices and collect mentor/community feedback, I created another Streamlit site to try different Kokoro voices and mixing options. We decided on about 5–6 default voices because each voice is roughly 0.5 MB and we wanted the activity to be lightweight. Additional voices could be downloaded from within the activity later via the Hugging Face Hub. I created a Streamlit benchmarking app to test the different voices and create new ones.

Here's a screenshot of the UI for this benchmark:

How voice combinations works

LLM benchmarking was fairly straightforward; most models performed well out of the box. The main area of focus was model guardrails and profanity filtering. We still made a benchmark so people could see how models performed.

Once the benchmarks were done, I started implementing the activity.

The challenge was getting Kokoro to stream audio into the existing audio pipeline. I won't dive deeply into the technical details here (see my GSoC weekly blogs on my site if you're interested), but a lot of resampling and other optimizations were needed to make previous features, like the mouth animation, work with the new audio. I also changed the fallback G2P engine for Kokoro from espeak-ng to espeak, since the previous version used espeak; this reduced additional dependencies for the activity.

Profanity filters and child-safety measures were important. The filters performed two checks: whether the child entered something profane, and whether the model output was profane. In both cases, the output would be intercepted.

Most SLM challenges were mentioned above. We chose a small model (~0.1B parameters), quantized it, and converted it to GGUF, and performed multiple rounds of fine-tuning. It was interesting to see how far the model progressed - in the beginning it could hardly understand English grammar.

This part wasn't technically the trickiest, but it had to be done carefully because it was the organization's first attempt to integrate AI into activities. At Sugar, we wanted a centralized way to integrate AI across activities - that's how SugarAI was born.

All API key management is handled by SugarAI; the activity just sends requests to SugarAI and receives responses. I was responsible for deploying SugarAI. It's hosted on a G5 instance on AWS and runs in a Docker container. I set up nginx and SSL certificates. SugarAI has two parts: serving the API and generating responses, and API key management.

During the summer I picked up and learned about SugarLabs' infrastructure. At one point we faced an issue with the wiki: the machine running it had problems and experienced significant downtime. We needed a way to increase uptime, so I suggested moving our nameservers to Cloudflare (there were other reasons for the move as well). Cloudflare offers features like Always Online, which can serve a cached version of your site from the Internet Archive if the origin is down. That means when the wiki server is down, the wiki can remain read-only instead of being completely unavailable.

This was a great learning experience: I learned how nameservers are changed and got to talk to people who manage SugarLabs' infrastructure (one of them works as a senior engineer at SpaceX!).

I enjoyed doing these infrastructure tasks alongside my GSoC project - it really got me hooked on how infrastructure is managed.

Overall, I really enjoyed my GSoC experience. I learned a lot, worked with amazing people, and met some really cool folks. I also got to work on a project I was passionate about and wanted to contribute to. It was a great experience and I would highly recommend it to anyone who wants to get involved in open source.

If you're interested in learning more about SugarLabs, check out their website. If you want to reach out to me, you can find me on my personal site or on my GitHub.

You can also shoot me an email at [email protected].

Powered Not An SSG 😎