Checkout the slide deck: Design For Millions - Mebin J Thattil

Designing services that can serve Millions concurrently is nothing short of an engineering marvel. The engineering behind such systems often goes unnoticed, but if you need to build such systems you need to have a look under the hood.

When building services that need to scale to millions of users, there are several fundamental objectives that must be achieved:

What is scalability? Simply put, it's how well your system can handle growth. This growth can manifest in several ways:

There are two primary approaches to scaling:

Vertical Scaling: Simply put, it's beefing up your current system and upgrading it's specs. Think of it as upgrading from a 2GB RAM server to 4GB, then to 8GB. While straightforward, this approach hits physical and economic limits quickly.

Horizontal Scaling: In this approach we add more machines to distribute the load. Instead of one powerful server, you have multiple servers working together. This is the approach that enables true large-scale systems.

The internet runs on protocols - mutual agreements on how systems communicate. As technology evolves, new protocols emerge that offer better performance, compression, or security. However, this creates a dilemma:

Better throughput

Older devices may not support these newer standards, meaning:

So we try to balance optimization with backward compatibility.

Reliability means keeping systems running at all times and preventing failures. This involves:

If all fails then the system must have a plan B where core services are still up but the other services can go down.

"If you can't measure it, you can't improve it." Observability is about understanding what's happening in your system at any given moment. This is achieved through:

The LGTM stack (Loki, Grafana, Tempo, Mimir) is a popular open-source solution for observability:

- Loki: Log aggregation

- Grafana: Visualization and dashboards

- Tempo: Distributed tracing

- Mimir: Long-term metrics storage

When failures occur (and they will), you need strategies to:

At scale, even small inefficiencies become expensive. Cost optimization involves:

Performance isn't just about speed - it's about consistent, predictable behavior under all conditions. This includes:

Let's dive deeper into scalability since it's the foundation of everything else.

Vertical Scaling (Scaling Up)

When your system starts running out of resources, the simplest solution is to upgrade the hardware. However, this approach has significant limitations:

Horizontal Scaling (Scaling Out)

Adding more machines to distribute load is the path to true scalability:

Core idea is, for example: At some point, it becomes cheaper to run two 4GB machines than one 8GB machine, and you get better reliability as a bonus.

To understand these principles practically, here is a small story that's hopefully more relatable

Bob starts simple:

- Rents a T2 micro EC2 instance

- Deploys a blogging website

- Everything works perfectly... initially

Bob's blogs go viral! Suddenly:

- Traffic increases 10x

- Memory fills up

- Website becomes painfully slow

- His friends yell at him

Bob's Solution: Upgrade to a 4GB instance (vertical scaling). Cost: $1/month increase.

The blogs become even more popular:

- Traffic increases another 5x

- The 4GB instance is maxed out

- Two options:

- 4GB → 8GB upgrade: $5/month

- Get a second 4GB instance: $2/month (2 × $1)

Bob's Realization: Horizontal scaling is more cost-effective! But this introduces a new problem: How to distribute traffic?

With two servers, Bob needs a load balancer:

- Health checks: Monitors if servers are responsive

- Traffic distribution: Spreads requests across healthy servers

- Automatic failover: Routes traffic away from failing servers

There are many ways to load balance an application, some common methods are - round robin, least connections, IP hashes.

Which method we choose depends on the use case.

Bob's friend in the US complains the site is slow. Why?

The Problem: Physical distance. Data travels at the speed of light, but:

- Network hops add latency

- Long distances mean longer round-trip times

- International routing can be inefficient

The Solution: CDN (Content Delivery Network)

A CDN caches content at edge locations worldwide:

- Static content (images, CSS, JS) served from nearby servers

- Reduced latency for users

- Lower bandwidth costs for origin servers

- DDoS protection as a bonus

Bob wants to add live streaming to his site. He immediately faces multiple challenges:

Bob realizes he needs to study how the experts do it. Enter: Hotstar.

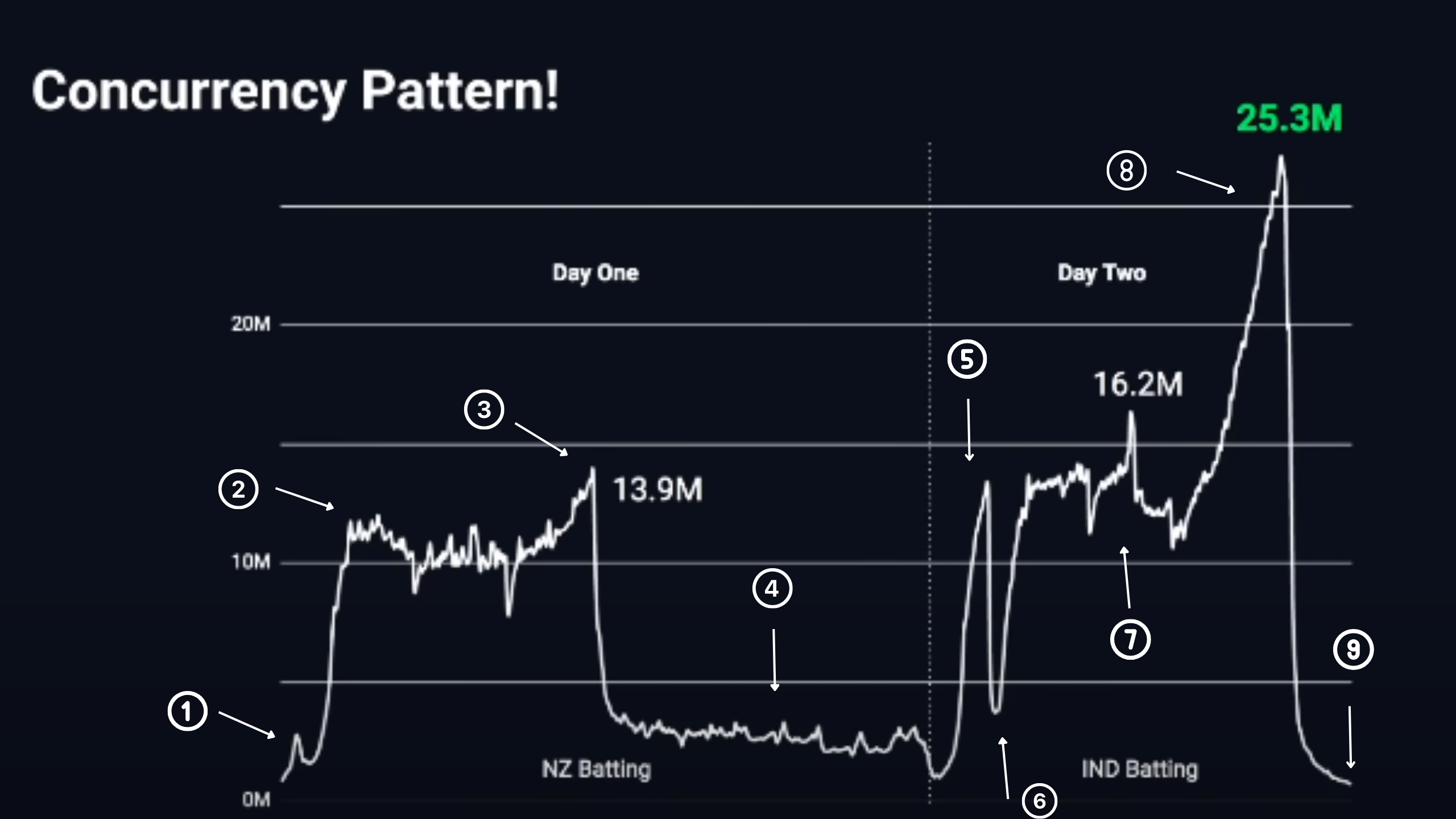

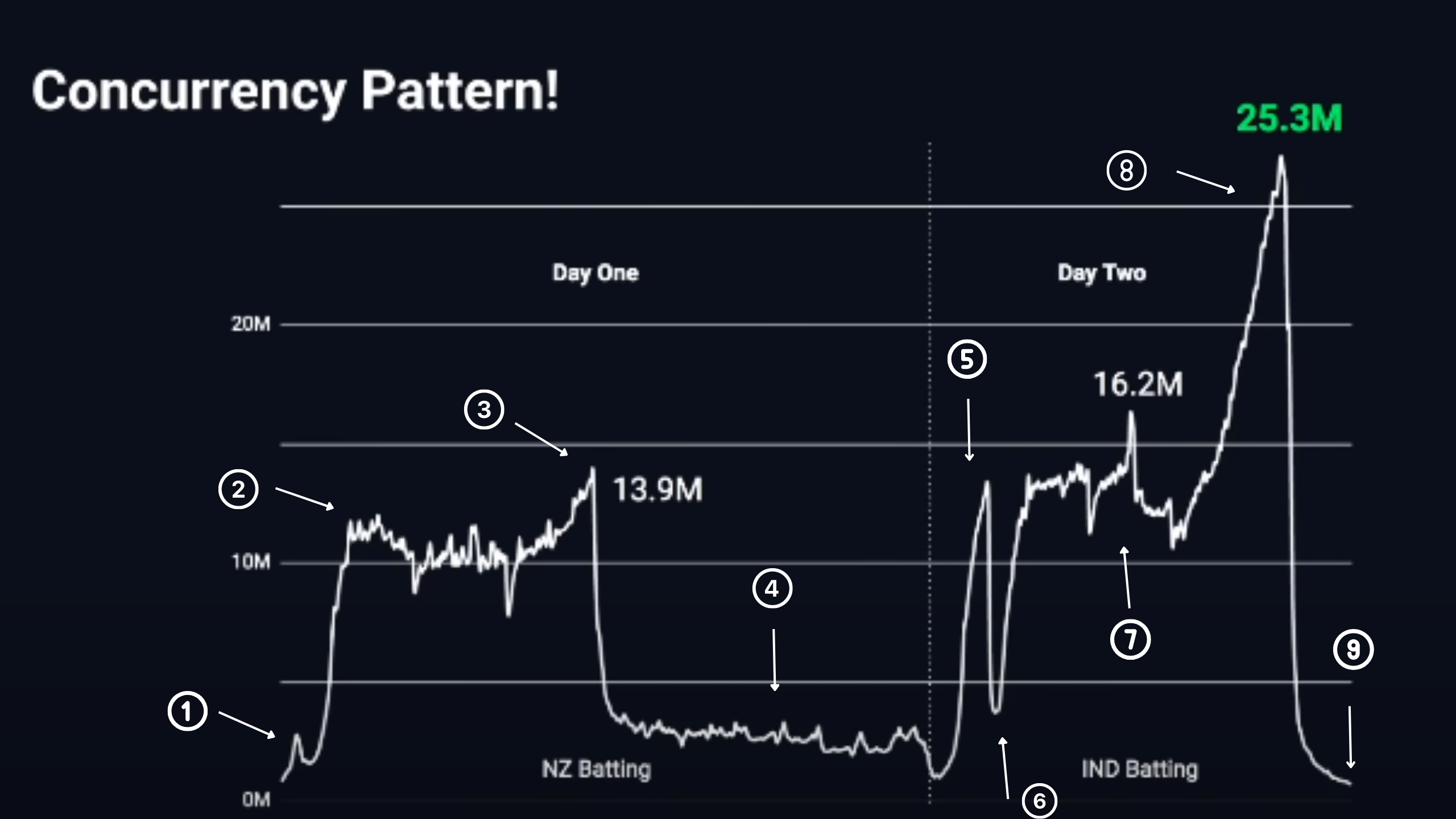

Hotstar (now JioHotstar) is one of the world's largest video streaming platforms. During the 2019 ICC Cricket World Cup, they achieved something unprecedented. They served a maxium of 25.3 million concurrent viewers 🤯. No platform had come close to this scale before.

1 -> Toss (beginning): 5-10M viewers tune in

2 -> Match Starts: Gradual climb to 15M viewers

3 -> Rain delay: 15M → 3M (most switch away)

4 -> Match Resumes: 3M → 15M in minutes (massive spike!)

5 -> Innings Break: Small dip

6 -> India batting: 15M → 20M+ (peak engagement)

7 -> Critical moments: Can spike to 25M+

8 -> Match ends: Rapid drop-off

The hardest part isn't handling 25M concurrent users - it's handling the rapid spikes and drops:

The Dhoni Effect: When Thala got out, viewership dropped from 25M to 1M in minutes. The system had to gracefully handle both the peak and the sudden decline.

Rain Resumes: When play resumed after rain, viewership jumped from 3M to 15M almost instantly. The system had to scale from serving 3M to 15M in under a minute.

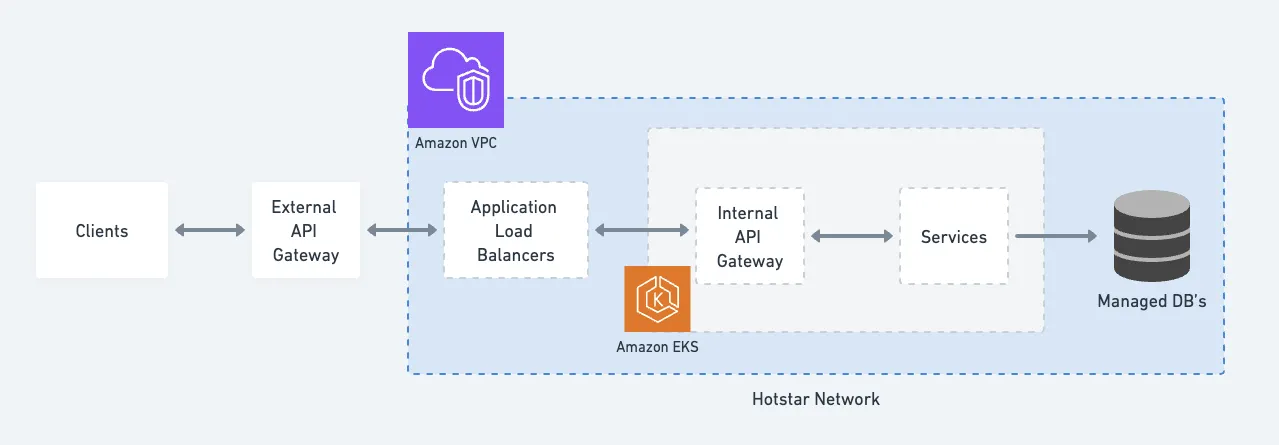

Hotstar's architecture is designed with multiple layers of redundancy and optimization:

External API Gateway (Akamai CDN):

- Security checks

- Rate limiting

- DDoS protection

- Request routing

Internal API Gateway:

- Sits behind Application Load Balancers

- Routes requests to appropriate backend services

- Handles authentication and authorization

Backend Services:

- Microservices architecture

Databases:

- self-hosted and managed DB instances

A eureka moment of figuring out that all requests need not be treated the same way helped optimize their systems.

The team realized they could segregate APIs into two categories:

Cacheable Content:

- Scorecards

- Concurrency metrics

- Key moments/highlights

- Match statistics

Non-cacheable Content:

- User-specific data

- Personalized recommendations

- Authentication tokens

- Real-time user interactions

By treating these differently, they could:

- Apply lighter security and rate controls to cacheable content

- Reduce stress on compute capacity

- Increase overall throughput

They created a separate CDN domain specifically for cacheable content with:

- Optimized configuration rules for cacheable paths

- Better isolation from core services

- Protection against misconfigurations affecting critical services

The Problem: At just 1/10th of peak traffic load, a single Kubernetes cluster was using 50% of the NAT Gateway's network throughput capacity.

Standard Setup:

- One NAT Gateway per AWS Availability Zone (AZ)

- All subnets route external traffic through that gateway

- This became a bottleneck at scale

Solution: Provision NAT Gateways at the subnet level instead of AZ level. This provided more network paths and distributed the throughput load.

The Problem: Network throughput analysis revealed:

- Some services consumed 8-9 Gbps per node

- Nodes running multiple internal API Gateway pods simultaneously created throughput spikes

- Uneven distribution caused some nodes to max out while others were underutilized

Solution:

1. Deploy high-throughput nodes (minimum 10 Gbps network capacity)

2. Implement topology spread constraints to ensure each node hosted only a single API Gateway pod

3. Result: Throughput per node stayed at 2-3 Gbps even during peak load

The Setup: Before the 2023 World Cup:

- 3 subnets across multiple AZs

- Each with /20 CIDR blocks (~4,090 IPs per subnet)

- Total: ~12,300 IP addresses

The Problem: They needed 400 Kubernetes nodes but couldn't scale beyond 350. Why? They ran out of IP addresses!

But wait - 12,300 IPs should be enough for 400 nodes, right? Not quite.

Understanding AWS ENI (Elastic Network Interface):

- Each Kubernetes node can run multiple pods

- Each pod needs its own IP address

- AWS pre-allocates IPs for faster pod startup (propagation takes time)

- This means each node requires multiple IPs to be reserved

Default AWS CNI Settings:

- MINIMUM_IP_TARGET: 35 IPs per node

- WARM_IP_TARGET: 10 additional IPs pre-allocated

So each node actually required ~45 IP addresses!

With 350 nodes × 45 IPs = 15,750 IPs required (they only had 12,300 available)

Solution:

1. Modified VPC CNI configuration:

- MINIMUM_IP_TARGET: 35 → 20

- WARM_IP_TARGET: 10 → 5

2. Added new subnets with larger /19 CIDR blocks (~8,190 IPs per subnet)

3. Result: ~48,000 additional IP addresses available

You can't just hope your system works at scale - you need to test it. Hotstar built an in-house load testing system called Project Hulk:

Specifications:

- C5.9xlarge EC2 instances

- Distributed across 8 AWS regions

- 108,000 CPUs

- 216 TB RAM

- 200 Gbps network output capacity

Purpose:

- Simulate millions of concurrent users

- Test system behavior under various load patterns

- Identify bottlenecks before the actual event

- Verify autoscaling and failover mechanisms

The Math: Imagine 1 million users join per minute:

- Application boot time: 1 minute

- EC2 instance provisioning + Load Balancer health check: 5-6 minutes

- By the time new instances are ready, 5-6 million more users have arrived

- Reactive scaling can't keep up!

Solution: Proactive scaling with buffers

Instead of reacting to load, Hotstar:

- Predicted traffic patterns based on historical data

- Pre-scaled infrastructure before expected spikes

- Maintained buffer capacity above predicted peak

- Had "ladders" defined: For X million users → provision Y servers

AWS Autoscaling has limitations at extreme scale:

Hotstar's Custom Solution:

- Scales based on RPS (Requests Per Second) and RPM (Requests Per Minute) instead of CPU/RAM

- Uses "ladders": Pre-defined rules like "for 10M users → 500 servers"

- Secondary scaling groups with more powerful instances as fallback

- Utilizes SPOT instances for cost savings

When things go wrong (and they will), you need a plan. Hotstar implements "Panic Mode":

Priority System:

- P-0 Services: Critical (must ALWAYS be up)

- Video playback

- Authentication

- Basic navigation

- P-1 Services: Important but not critical

- Detailed statistics

- Commentary

- Social features

- P-2+ Services: Nice-to-have

- Recommendations

- User profiles

- Historical data

During Panic Mode:

1. Turn off non-critical services (P-1 and below)

2. Redirect all resources to P-0 services

3. Bypass certain checks if necessary to keep core services running

4. User experience degrades (fewer features) but doesn't disrupt (service stays up)

This ensures that even in worst-case scenarios, users can still watch the stream.

Let's understand how video streaming actually works, since this is core to Hotstar's service.

The magic of modern streaming is ABR - the ability to adapt video quality based on network conditions:

How It Works:

1. Encode the same video at multiple bitrates (qualities)

2. Client player monitors available bandwidth

3. Player automatically switches between quality levels

4. Seamless viewing experience without buffering

Example: If you're watching on fast WiFi at 1080p and switch to cellular, the player automatically drops to 720p or lower to prevent buffering.

HLS (HTTP Live Streaming):

- Developed by Apple

- Uses standard HTTP

- Works with any CDN

- Good device compatibility

- Segment-based delivery (.ts files)

- Manifest files (.m3u8) describe playlist

RTMP (Real-Time Messaging Protocol):

- Legacy protocol

- Used primarily for ingestion (from encoder to server)

- Being phased out in favor of modern alternatives

There are various codecs available such as: H.264(AVC), H.265(HEVC), VP9, AV1

This is where compatibility principles come into play:

At Hotstar's scale, even small bandwidth savings multiply enormously:

- 1 MB saved per user per hour

- 25M concurrent users

- 3-hour match

- = 75 PB of bandwidth saved!

Building systems for millions requires thinking differently:

Re-architecting systems once you're knee deep is much harder than building them right initially.

You can't improve what you can't measure. Try to setup observability tools early on.

Failures will happen. Design systems that:

- Degrade gracefully

- Isolate failures

- Recover automatically

- Maintain core functionality

At scale, small inefficiencies become expensive. Try to be as efficient as possible.

You can't know how your system behaves under load until you test it. After testing identify the bottlenecks and fix those.

Not all requests are created equal:

- Identify cacheable vs. non-cacheable content

- Apply appropriate security based on sensitivity

- Create isolation between critical and non-critical services

- Optimize each category separately

Manual scaling doesn't work at this level:

- Automate provisioning and deployment

- Implement intelligent auto-scaling

- Build self-healing systems

The engineering behind services like Hotstar is a testament to careful planning, continuous optimization, and learning from real-world challenges. While not every application needs to handle 25 million concurrent users, the principles remain the same:

Both Bob's simple blog and Hotstar's massive infrastructure illustrates that scaling is a continuous process. You start simple, identify bottlenecks, solve them systematically, and iterate.

No one builds a perfect system on day 1. Build systems that evolve.

Want to experience scaling challenges firsthand? Checkout this cool game I found (disclaimer: it's super addicting):

Server Survival Game

This blog post is based on the presentation "Design For Millions" I gave at Talks@ACM 2026.

Powered Not An SSG 😎